Theoretical Foundation

The “Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization” (LCC) is based on really simple foundations. Firstly, George Russell identified the fifth as the strongest interval. Of course this is not a novel observation; the fifth is generally regarded as being more consonant and stable than any other interval. However, Russell took this basic observation and formulated a set of ideas around it, not the least of which is the consequence of creating a scale based on a ladder of ascending fifths. More on that shortly.

“The establishment of the fifth as the strongest harmonic interval represents the most important contribution of the overtone series to the fundamental principle of the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization – the Principle of Tonal Gravity.” 1

You can see from the quote above that identifying the fifth as the strongest interval was really important to Russell because it led him to two fundamental concepts: the “overtone series”, and the principle of “tonal gravity”. Let’s take a look at those next.

Overtone series

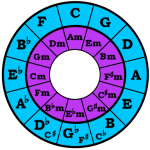

If you take the interval of a fifth and stack 6 of them on top of each other you derive a series of 7 notes. This is easy to visualise using the cycle of fifths (left). Just divide the circle in half from any note and move clockwise.

If you take the interval of a fifth and stack 6 of them on top of each other you derive a series of 7 notes. This is easy to visualise using the cycle of fifths (left). Just divide the circle in half from any note and move clockwise.

Take C as an example root note.

C - G - D - A - E - B - F#

This set of notes derived by stacking fifths from a root note is the “harmonic series”. If you reorder the notes alphabetically you get the following.

C - D - E - F# - G - A - B

What scale is that? Well, the notes are I-II-III-#IV-V-VI-VII. This is the Lydian scale and not the major (Ionian) scale.

Now compare C Lydian with C major (Ionian):

Lydian: C - D - E - F# - G - A - B Major: C - D - E - F - G - A - B

The only difference is the fourth, F. In comparison to the major scale the Lydian fourth is raised a semitone. This small change has a really interesting and positive effect.

In the major scale the fourth is problematic because it creates an unpleasant dissonance when played against the diatonic C chord, Cmaj7. If you add the fourth (or the eleventh because it’s the same thing) to a major 7 chord it creates a nasty sounding minor 9 interval against the third of the chord, E. This doesn’t happen in the Lydian scale because the fourth is raised a semitone.

Mark Levine, in his book on jazz theory, confirms the problem of the fourth in the major (Ionian) scale by referring to it as an “avoid note” when harmonising the scale.

Go to a piano and play a root position [Cmaj7] chord with your left hand while playing the C major scale with your right hand… There is a note in the scale that is much more dissonant than the other six notes. Play the same chord again with your left hand while you play the 4th, F, with your right hand… This is a so-called “avoid note”. 2

Because the Lydian scale has a raised fourth it doesn’t have an avoid note.

Examples

Here’s an example of Cmaj7 with the fourth (or 11) on top.

And now an example of Cmaj7 with the raised fourth (or #11) on top.

And just to round things off here is a comparison between all the notes the overtone series with a fourth (IV) on top – as in the major scale – and then the raised 4th (#IV) on top – as in the Lydian scale.

Notice the first chord is quite dissonant whereas the second chord has a pleasing open sound to it. The second chord is actually Cmaj13(#11) which is the result of simply playing all the notes of the harmonic series – and therefore the Lydian scale – at the same time.

Tonal gravity

Russell talks about the “Lydian tonic” rather than the usual major scale tonic note. To Russell, there is a tendency for music that follows the LCC to want to move down the overtone series towards the Lydian tonic.

Tonal Gravity, or “tonal magnetism,” within a stack of intervals of fifths flows in a downward direction. 3

This is no surprise; it’s consistent with back-cycling the cycle of fifths to create strong root movement. I covered that in a post on strong root movement.

The Lydian scale is inherently consistent with back-cycling; you can back-cycle indefinitely using all the notes in the scale. You can’t do that with the major (Ionian) scale because of the perfect fourth. Looking at the C example, if you wanted to back-cycle from the B you would need to go to F# which is not in the major (Ionian) scale. However, the raised fourth of the C Lydian scale is an F# and that fits right in.

Goal orientation

We have seen in previous posts about chord families and strong root movement how we create forward motion in music – at least in music based on the major scale – through a process of creating tension and then releasing or resolving it. Russell recognises this process and calls it “horizontal motion”.

In fact, Russell defines the nature of the major scale as:

THE STATE OF BECOMING A FINALITY – the state of linear, horizontal goal orientation; the state of permanent tension 4

As I understand it, Russell is saying that music based on the major scale is by nature always in a state of creating and resolving tension with that need to resolve representing the “goal”. By contrast he sees the Lydian scale as lacking this tension but flowing naturally down the stack of fifths to the Lydian tonic. Of the Lydian scale he says:

THE STATE OF BEING A UNITY – A unified tonal gravity field in which gravitational energy is passed down a ladder of fifths to its lowermost tone: the Lydian Tonic. 5

Basically, what Russell is saying is that the Lydian scale lacks the goal orientation of the major scale. The major scale results in tension that wants to resolve to the major scale tonic (e.g. chords can be grouped into families with different properties leading to sub-dominant to dominant to tonic chord movement). The Lydian scale lacks this because each note just wants to resolve to the previous note in the harmonic series.

He refers to the Lydian scale as having a vertical nature rather than the major scale’s horizontal nature and describes the state of unity present in the Lydian scale. As I understand it, “unity” refers to how each note in the Lydian scale has an equal tendency to resolve to the previous note in the harmonic series.

Wrapping up

Russell goes in to much more detail than that given above but these are the key take-away points for me:

- Creating an overtone series by stacking fifths on top of each other gives you the Lydian scale, not the major scale.

- Moving down the overtone series is equivalent to back-cycling the cycle of fifths to create strong root movement.

- The fourth in the major scale is an avoid note. This is not an issue with the Lydian scale because of the raised fourth.

- The Lydian scale lacks the tension inherent in the major scale by existing in a state of unity.

Here’s a video by Walk That Bass on YouTube covering similar ground:

To Russell, the features of the Lydian scale make it a more “scientific foundation” for a theory of music than the major (Ionian) scale, a theory Russell called the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organisation.

But it doesn’t end there! Russell goes on to explore what happens if you add additional fifths beyond the octave to the overtone series and derives a set of scales including those extension notes. We’ll start covering that in the next post.

Next (Part 3 – The Seven Principle Scales)

Back to Part 1 (index to posts in the series)

References

- Russel, G (2001). The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, 4th Edition, p.3

- Levine, M (1995). The Jazz Theory Book, p.37

- Russel, G (2001). The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, 4th Edition, p.3

- Russel, G (2001). The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, 4th Edition, p.7

- Russel, G (2001). The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, 4th Edition, p.8

Looking at your article I would generally agree until you write about the major scale. ‘The major scale results in tension that wants to resolve to the major scale tonic (e.g. chords can be grouped into families with different properties leading to sub-dominant to dominant to tonic chord movement).’ Not really. I don’t see it like that, Russell states that the major scale is a scale of duality. That is, the lydian tonic (F in C major) is always trying to assert itself over the major tonic. This is what causes the tension and goal orientation. However, Russell does not… Read more »

Thanks again for to comment, Andrew. Contributions are always welcome. For any other readers who stumble across this post I reaffirm that, as stated in part 1 of this series, that I am no expert. This is my blog and merely a record of my investigations into music. Treat everything here with that in mind. That said, I don’t follow your objection to the passage you quote (“The major scale results in tension that wants to resolve to the major scale tonic…”). Russell himself states: “The major scale represents the horizontal, music active force forever in a state of resolving… Read more »

I see where you are coming from in this comment. This is Russell again. Yes looking at the music from the point of view of the major scale tonality you get the statement Russell makes above which I agree with (to a point); in fact Reed Gratz in his (Russell’s) book go’s on and on about the development of the major scale being because society is one of striving and tension – which I don’t agree. However, if you look at the major scale (horizontal playing) from the point of view of the LCC you end up with Russell seeing… Read more »

I think there is a slight error in the text.

I think you meant to put the G after the F and F#.

Otherwise, this is a great article. Thank you for the time you put in here.

Regards,

Jim.

You are absolutely correct, Jim. Thanks for taking the time to let me know. Much appreciated! I have made the correction.